Arts and environmental initiatives have driven a campaign to attract wealthier residents to the riverfront city. It could be a sign of things to come in the Hudson Valley.

Successful civilizations have often been built around bodies of water. Water is the lifeblood of human survival—and, by extension, industry. As a result, the land along coasts has been justification for colonialism and expansion.

The land Yonkers was built upon was once Lenape territory, and has long been fueled by trade along the Hudson River. The industry that developed was powered by the mills along the Saw Mill River, which empties into the Hudson. Factory dumping left the Saw Mill so polluted that when it no longer served the purpose of powering the mills, it was cemented over. In 2010, Yonkers carried out a $48 million daylighting project to remove the flume beneath the pavement that the river flows through and bring the river back to the surface. The project uncovered the river for six blocks in downtown Yonkers—and once again, development was drawn to water. The uncovering of the Saw Mill River has brought about the claiming of land in a kind of neomanifest destiny.

The park at the site of the daylighting was cosponsored by an environmental nonprofit: Groundwork Hudson Valley. Groundwork’s participation in the daylighting site was controversial, and sentiment from Yonkers locals was mixed. On the one hand, the daylighted Saw Mill River was new habitat for wildlife, and a place for the public to gather and enjoy nature. On the other hand, the presence of the new and attractive park sped up development significantly, driving property values up. One local student told me, “They keep saying this is our park. It’s not—it’s Mayor Mike Spano’s park.”

The revitalization of green spaces is part of the present-day land grab of downtown Yonkers. Property values seem to rise in proportion with the number of attractive public spaces nearby. “Businesses definitely have the upper hand,” says Roger Osorio, a former Groundwork employee. “They’re bringing in money and repairs to the areas that have been neglected.”

Osorio has a warning for other Hudson Valley cities: “Newburgh has been at it. They are far removed enough to observe what’s happening in Yonkers and prepare. Green spaces for us were the first step.”

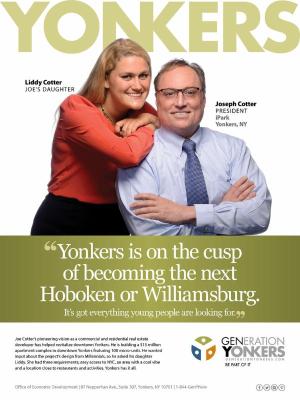

There are now three daylighting sites that take up six blocks of downtown Yonkers, including Chicken Island, named for the slaughterhouse that once stood in the area. In late October 2018, Yonkers Mayor Mike Spano announced that the city would sell the Chicken Island parking lot. AMS Acquisitions of New York City agreed to buy the six-acre lot and develop it into a mixed-use residential center that would include a luxury hotel. That followed a nearly 40-year attempt by the city and private developers to develop the area into an accessible environment for those fleeing the five boroughs to Westchester County. This “sixth borough” strategy is a hallmark of the Generation Yonkers campaign, an economic development plan intended to appeal to young professionals and couples looking for easy access to New York City for work and entertainment, without having to pay city rent. Its slogan: “Attracting a whole new generation of visionary business leaders and residents.”

Then COVID-19 happened, and now those fleeing the city amid the pandemic are now moving further up into the Hudson Valley where they will be able to work remotely.

Many Yonkers locals do not have that option. The city has a significant number of immigrants, people of color, low-income families, and essential workers who have been impacted by the pandemic. These demographics are particularly vulnerable to medical racism as well as being more likely to be essential workers, putting them at heightened risk of catching COVID-19. Busy schedules also limit their ability to intervene in plans set at public city council meetings, even before the pandemic.

The desperation of low-income citizens has driven many to relocate to Mount Vernon or New Rochelle for the marginally lower cost of living. At the same time, New Yorkers looking to escape the impact of the pandemic in New York City can easily move to a cheaper and more spacious home in Yonkers and continue to work remotely without fear of transmission brought on by a subway commute.

Many of the people I interviewed for this piece brought up Yonkers’ infamous history of segregation and redlining, and saw efforts to develop the waterfront as a repetition of that history. Artist and activist Shanequa Benitezhas seen a dangerous and predatory pattern that keeps property values low until they can be flipped by developers.

“In order to gentrify an area, there are a few things that have to happen,” Benitez explains. “You have to drive the crime rate up. There’s an influx of drugs and everybody gets indicted, huge sweeps with people getting 15 to 20 years. Then, the homelessness rate goes up and you have methadone clinics and homeless shelters right next to the places they are trying to fix. That makes it an undesirable location and keeps the property value low. The homelessness downtown is out of this world right now. People are dying outside. You ever notice when they finish gentrifying a place, the homeless people disappear? It’s just another way to redline an area.”

Artists like Benitez have a unique perspective on gentrification, as the revitalization of arts spaces is often one of its first steps. She notes how outside artists get brought in to make an area attractive while local artists go unappreciated. “When I’m showing my work in the new downtown Yonkers that doesn’t reflect me, I feel like I’m low-key tap dancing,” she says. An influx of new artists lends an area aesthetic beauty, culture, and the ever-important cool factor, which often leads to what real estate developers might call “revitalization” and low-income residents might see as a threat to their very existence in a neighborhood. This puts community artists like Benitez and so many others in a difficult position.

***

Walking through downtown Yonkers feels like passing in and out of several dimensions. People playing mixtapes on old-school boomboxes for yuppies having coffee in outdoor, socially distanced seating. Skaters dodging potholes towards a newly paved public park complete with Lime bikes. Police harassing Black joggers along the waterfront. Murals painted on the sides of formerly abandoned factories turned luxury lofts.

The transformation of abandoned infrastructure to meet new needs is what property flippers call “good bones.” In Yonkers, that means the elevator factory becomes a modern loft space, the carpet mill becomes artist studios, the old Putnam railroad line becomes a biking greenway. Little attention is paid to how these spaces became abandoned in the first place, much of which has to do with the ugly history of redlining, white flight, and the decline of industry. The same pattern well underway in Yonkers is already affecting other former industrial cities along the Hudson such as Poughkeepsie, Newburgh, and Kingston.

Much of the appeal of living in former factory cities are the cool, renovated buildings that have been transformed. Take the UNO Apartments, a building that was renovated from the old Otis Elevator Company factory that made Yonkers famous as a manufacturing hub. The outside of the UNO building shares a wall with the Yonkers DMV, where a bright yellow mural was one of the first pieces of public art in the downtown area. The UNO developers have since used the mural in nearly all their marketing, taking advantage of the iconic yellow background. None of the apartments is conducive to living with a roommate; they are best suited for young singles or couples, few of whom can afford the $1,500 minimum rent. Even still, the building is nearly full.

UNO is just one of the massive flipping projects to happen in Yonkers in recent years. The more-than-140-year-old Alexander Smith Carpet Mills is now home to the YoHo artists community. The ruins of the mill include 85 buildings, many of which were condemned until the arts district was approved by the Yonkers city council in 2016. The district received a $500,000 capital grant for renovation of parts of the mill to be used as galleries, studios, and work spaces. Abandoned buildings like these have never seriously been considered for renovation into low-income housing or homeless shelters due to insistence by city officials that doing so would be too costly. Investment in community projects is only considered viable by the city government if it contributes financially and aesthetically to the vision of Generation Yonkers.

In 2013, art collector Daniel Wolf and his wife, architect Maya Lin, purchased the Alexander Street Jail in Yonkers for $1 million, less than half of the asking price of $2.6 million. The goal was to sell the building as part of the effort to revitalize the waterfront. As Mayor Spano said at the time, “the waterfront should be a place to shop, live, or walk…It’s not the right place for a jail.” After a series of tax breaks, the couple ended up paying $729,937 for the 10,000-square-foot waterfront property. In exchange for the significant discount, Wolf and Lin agreed to host public arts events in the space. This never happened. Instead, the human beings that were held in the facility until its purchase were relocated to larger correctional facilities to make room for and securely hold portions of a valuable, private art collection that is inaccessible to the public.

Despite city government investment in art spaces, young multimedia artists like Malik Lamont Yancey have found it difficult to thrive in the new Yonkers art scene. When I met Yancey in 2018, he was still a high school senior and one of the founders of an artist collective called “NEO,” composed of students from all over the city. Many NEO members came to the group’s after-school meetups at the Yonkers public library because it was a safe space to spend with community on Friday afternoons. Yancey and his cohort were all confident, stylish, cool, and completely talented. They seemed destined for something greater than what the city could offer them at the time.

Back then, Yancey believed that in order to be taken seriously as an artist, he would need to leave Yonkers. He still does. “I’m trying move to New Mexico or something like that. I need something different,” he tells me. He goes on to explain how he never saw people claim Yonkers making it even harder to convince them to take the community back from outsiders. “I don’t want to hate, but folks don’t have the money or mentality to fight for Yonkers,” he says. “So when someone comes offering to buy a building for less than it’s worth, they get bought off easily while selling other people on what the city will look like after it’s gentrified while it’s still cheap.”

Yancey says he spends a lot of time in New York City now, though he still lives in Yonkers. He has an internship at a clothing brand and does not see much of a scene for young artists in Yonkers. It is easy to forget what one loves about home when working to make it into a place you know your community deserves feels fruitless.

***

It is hard to escape the irony that the view of the Hudson River from Buena Vista Avenue in Yonkers is now obscured by rows of high-rise waterfront properties that sit nearly empty. When the urban farmers of Yonkers got word that the vacant space nearby, which had been home to a thriving community garden for over 20 years, would soon be paved over to make a parking lot, their feelings were not anger but rather regret and resignation. It seems that the existence of such a space for so long was miraculous in and of itself to those who worked it: a space where city children could bury their hands in the earth, sow their own seeds and watch them grow season after season. So long that some of their children could one day be the next stewards of the small patch of land.